On this day twenty years ago, the department at the bank where I worked in downtown Dallas experienced a catastrophic system disruption. I was an associate in the funds transfer division’s customer service unit. I helped our clients with whatever problems arose regarding their domestic and international financial transfers. As a moderately large institution, the bank processed millions of dollars on a daily basis; sending money all over the country and all over the world. With a few exceptions, things operated relatively smoothly.

The 1993 bombing of New York’s World Trade Center had made bank officials realize the stark vulnerability of its various operations. A large New York-based financial institution housed its funds transfer division in that same tower. But they had a back-up outfit established in a location several miles away. Thus, when the truck bomb exploded, the company was able to switch operations to their satellite office and proceed normally – all other things considered.

Shortly thereafter, my employer rushed to create similar back-up protocols for every division. The wire transfer department established an office in suburban Dallas and assigned certain individuals to staff the location in the event of an emergency. I was one of those designated associates.

Then came April 2, 1996, and the most curious of incidents occurred; one for which the bank actually hadn’t planned. There was no bombing; no monster tornado; no building power outage; no gunman; not even the vending machines ceased operating, which would have certainly caused a riot among the employees. (I mean, if you can’t get a Coke or a Snickers after dealing with bitchy customers, how else can you get through the day?)

The event was just shy of a total system collapse. The company had two communication lines with the Federal Reserve Bank: one for transmitting outgoing payments and the other for incoming. Shortly after 10 a.m. local time, the outgoing line inexplicably short-circuited. The incoming line functioned properly throughout the entire day. Even more inexplicably is that company programmers – the people paid thousands of dollars to create and maintain these systems – couldn’t figure out what happened with that outgoing line. As we learned later, they didn’t take the problem too seriously at first. They apparently thought it would right itself without further delay and much intervention. This is akin to contemporary tech support people saying, “Just reboot,” when you experience a computer problem. It’s a step above the ‘Press any key’ command.

The programmers were wrong. By noon that day, panic had started to settle into everyone’s minds. Well… not us lowly non-managerial associates. We were not apprised of the seriousness of the matter – as usual – and instructed to tell customers – as usual – the bank was working on it and had everything under control. Those of us occupying the lower rungs of the corporate food chain (the folks who don’t own the dairy, but milk the cows) really had no idea of the situation’s gravity until late in the day.

By the time those highly-paid programmers finally rectified the crisis, it was too late. It was after 6 p.m., and the Federal Reserve had to stop processing wire transfers. Literally millions of dollars in customer funds – corporate and individual – had not left the bank. It was bad enough to affect interest rates on a national level for that day. Even the president of the United States was made aware of the crisis.

It didn’t help that the event occurred as the first anniversary of the Oklahoma City bombing approached, and people were growing more concerned about the pending Y2K disaster. That following Friday morning the wire transfer division held its usual quarter end meeting. My unit manager addressed the crowd by saying, “You know we can’t get through today without discussing April 2.” Technically, the day fell at the start of the second business quarter. But, like an all-you-can-eat buffet after a week at a diet camp, it was too good a deal to pass up. They had to talk about it. This is where it went from bad to whimsical; the latter courtesy of yours truly.

One woman, some forgettable high-ranking bank official who I’d never seen before, instructed everyone on how to respond to customer inquiries about “The Event.” She tried to explain that we shouldn’t get too detailed about what happened and certainly not offer any specific compensation. That’s what she tried to say. But, you know, things always look so damn good on paper. As a writer, I would have been more than happy to help her compose her frazzled thoughts into a coherent, practical speech. But, as a lowly cow-milker, she didn’t seek my advice. Instead, the verbiage that tumbled from her perky lips sounded like we should just pretend nothing happened on April 2.

I immediately began chuckling, which drew the attention of those around me. Then I started laughing, which drew even more attention. And, in that gathering of some 200 business professionals, I leapt to my feet and loudly interpreted: “Okay, everybody, we impacted interest rates across the country for a day! The president of the United States knows what happened! But – sh-sh – don’t tell anyone about it!”

More laughter ensued from the crowd. The woman standing up front tried to interject, but it was futile.

“So, here’s how you handle the call,” I continued, holding a phantom phone receiver up to my ear. “‘April 2? What about April 2? I have no idea what you’re talking about. Get off the phone!’”

The room erupted. Even the cadre of executives lined up at the front like a WestPoint brigade – including that one woman – were laughing. They all got the message: there was no getting away from the severity of “The Event.” All the back-up protocols they’d set in place three years earlier had failed to consider this mess.

That day is lost in the annals of financial history and pales in comparison to the catastrophe of September 11, 2001. When the two largest buildings of the World Trade Center were attacked with – of all things – large jet liners and collapsed, survival was the immediate concern for anyone nearby. As the dust cleared and the tears fell, scores of businesses realized that, amidst the carnage, they had also lost real estate space, phone lines and reams of data.

But, just as the nation recovered from that horror, the Northeastern corridor experienced a massive blackout on August 11, 2003. It reached as far as west as Ohio. Some 50 million people were directly impacted in a disaster that lasted more than a day. It reminded many of the 1977 New York City Blackout, which was equally reminiscent of the 1965 “Great Northeast Blackout.”

How could any of these things happen to one of the largest, wealthiest and most powerful nations on Earth? It’s not enough to wonder if you’re going to have a rough commute home from work. A Category 5 hurricane poses a serious threat to any coastal community. But so does a long-lasting power outage from the failure of an overworked, under-maintained facility.

At the start of this blog four years ago, one of the features was the “Mayan Calendar Countdown,” my humorous homage to the impending apocalypse of December 21, 2012. It was all in good fun, but I included many authentic survivalist tips. Some were obvious: guns and power generators; others were practical: canned meat and knives; a few were almost laughable: chocolate and gold bullion. It really does make sense, however, to have your own power generator and a water treatment device. You don’t have to be part of a right-wing extremist group to understand the vulnerabilities inherent in computer systems and crumbling interstate highways. Donning military fatigues and playing war games in some wooded area isn’t required to be prepared for power failures that may last for weeks or even months.

Some people lose it if their Facebook page gets hacked. I’d love to see them react to reddish-brown water pouring from their faucets – which doesn’t stop. In developed nations, we expect such water to flow clearly and purely; air systems to pump out warm or cool breezes; microwave ovens to function on queue – all with little effort on our part. People who are mortified by a gluten-filled sandwich would probably die if they had to catch a fish in a stream, gut it and then cook it on a rock.

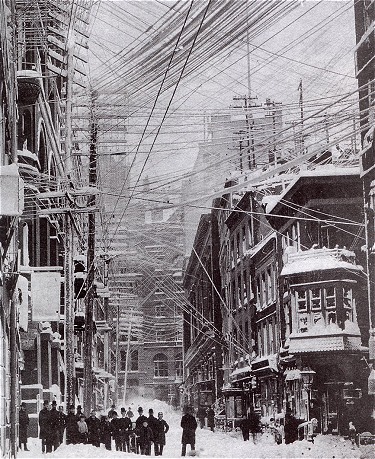

In March of 1888, a powerful blizzard slammed the Northeastern U.S.; a calamity that killed more than 400 people and dumped as much as 55 inches of snow in most areas. A blizzard is actually an arctic hurricane, which strikes with the same level of ferocity as their tropical counterparts. Canadian and European meteorologists name them, too. At the time of the “Great Blizzard of 1888,” roughly 1 in 4 Americans lived in the area between the state of Maine and Washington, D.C. Temperatures across the Northeast had been in the 50s on March 10, 1888. But, when the storm arrived the following day, wind gusts reached 85 miles per hour in some locations, and temperatures plummeted to below freezing within hours. The largest metropolitan areas in the region – New York, Washington, Boston – came to a virtual standstill amidst the whiteout conditions. Many residents tried to carry on as usual, but found mass transportation systems paralyzed by the heavy snow. Venturing outside became perilous. Wall Street had to shut down for 3 days. Mark Twain was in New York City at the time and became stranded at a hotel. P.T. Barnum also got stuck and – always the showman – took the opportunity to entertain fellow refugees at Madison Square Garden.

Near coastal areas, many ships and other vessels sunk in tumultuous waters the storm had generated. Thousands of farm and wild animals froze to death. Telecommunication lines collapsed from the heavy winds and / or weight of the snow. Gas and power lines malfunctioned. From this event and the catastrophic impact it had on train lines, the concept of the subway was born.

Strangely, though, people living in rural areas fared better than their urban counterparts. City folks had already come to rely (too much) upon electric lights and trains that ran on time. Yes, those rubes out in the sticks – living in wood frame abodes with kettle stoves – also suffered the storm’s wrath. But they were used to such treacherous weather. They prepared year-round for it. They never took for granted their ability to deal with the worst nature had to offer, or expected human-made objects and structures to protect them fully and completely. They just dealt with it as best they could. Most of the fatalities occurred within the confines of the mighty urban menageries. The places people deemed civilization couldn’t handle the wintry onslaught.

The “Great Blizzard of 1888” paralyzed the urban centers of the Northeastern U.S., such as New York City.

They often still can’t. Witness the horrors of 2005’s Hurricane Katrina. The city of New Orleans, in particular, wasn’t as prepared for such a calamity as officials had proclaimed for years. It wasn’t so much due to poor infrastructure, but rather to poor social and political structures. Entrenched corruption and poverty had made the city as vulnerable as the fact most of its geography sat below sea level.

By contrast, Japan, as a whole, has prepared itself well for every imaginable disaster, from earthquakes to volcanic eruptions. But that degree of security and confidence was shattered on March 11, 2011, when a 9.0 earthquake rocked the northeastern part of the country. Residents in coastal communities knew the dangers inherent with aftershocks and accompanying tsunamis. Entire cities and towns had staged regular evacuation drills for years. (At that bank where I worked, fire drills involved people sauntering into the hallway for a few minutes. On more than a few occasions, some folks just didn’t make the time for it and remained at their desks.) In northeastern Japan, many towns had constructed walls up to 30 feet (9.144 m) high along their shorelines to ward off or at least circumvent tsunami waves. But, when the waves inundated coastal towns, reaching further inland than even the experts anticipated, authorities wondered where they’d gone wrong in the planning. They didn’t anticipate that subsidence would cause the ground beneath the tsunami-protection walls to drop; thus, abruptly shortening their height. The trauma continued when the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant malfunctioned, generating the worst nuclear power accident since Chernobyl. Much of the area hasn’t been repopulated. Sometimes, that’s actually a more practical, albeit psychologically painful, recourse; more sensible than trying to outwit nature’s more destructive elements. After a powerful tsunami ravaged Hilo, Hawaii in May of 1960, some sectors of the city closest to the shoreline remain abandoned and were subsequently reclaimed by nature.

It would be impractical for residents of the Dallas / Fort Worth metropolitan area to move because of the constant threats of hail storms and tornadoes. Northeast Texas lies at the southern end of “Tornado Alley;” a dreaded meteorological vortex where the weather is reliably unpredictable. Just recently this region of some 10 million people learned of the fragility of the Lewisville Lake Dam; a massive, mostly earthen structure that sits north of Dallas. An increasing number of rock slides in recent years have eroded the dam’s integrity. There’s a very real threat of total collapse, which could kill thousands and inundate most areas up to 50 feet (15.24 m). At full capacity, the dam holds up to 2.5 billion tons (2.268 metric tons) of water. My parents and I live just a few miles south of it. It would be almost impossible for us to escape in a vehicle should a massive breach actually occur. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers claims it needs millions of dollars to repair the dam, which has now become one of the nation’s most dangerous. The U.S. government – which miraculously found billions of dollars to fund the Iraq War – can’t seem to locate any cash for the damn dam. So far, officials are making do with what they can: placing sandbags and tarps to thwart any further erosion. I wonder if there’s such a thing as industrial-strength duct tape.

Whenever a major disaster strikes – natural or human-made – people will get hurt and people will die. There’s no way to avoid it. It’s going to happen. It’s frustrating enough if you can’t get cash out of a local atm; it’s downright terrifying if you can’t get fresh water from your kitchen tap. More people reside in urban areas now than ever before in human history. And thereby, fewer people know how to catch and kill their own food or purify their own water. What happened to the bank where I worked on April 2, 1996 seemed emblematic – at the time – of the impending Y2K disaster. We got past that crisis and survived the non-existent 2000 implosion. It’s no laughing matter, though, when something even more cataclysmic jeopardizes tens of millions of people.

Tsunami waves inundated Sendai, Japan on March 11, 2011; reaching further inland than anyone expected.

Check out “The Survivalist Blog” for authentic tips on preparing for the worst.