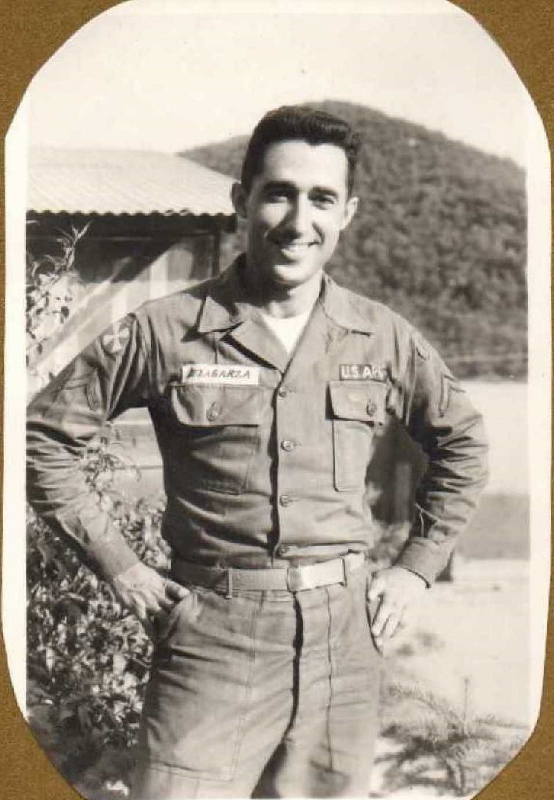

My father in 1949 at age 16.

At one family Christmas gathering in the 1980s, someone had invited an older couple most everyone knew. They often provided musical entertainment at such gatherings; with the man playing a guitar, while he and his wife sang. During this particular evening, the woman brought out a set of maracas and began yodeling. I have to concede that – up to that point – I had never heard a Mexican yodeling. I always thought yodeling was a characteristic unique to people only of Nordic extraction. Even though I’m one-quarter German, I don’t possess such a talent. But, if you’ve ever heard a Mexican yodeling…well, imagine a Chihuahua having a Maalox moment from hell.

Some of my male cousins and me tried to sustain our laughter and wondered how long this would continue. The gathering took place in the house of one my aunts, Teresa, and her husband, Chris. A massive abode with a wide, marble-laden foyer, a living room or seating area sat off to the left upon entering, and a formal dining room to the right, which allowed entry into the kitchen. Most everyone had gathered in the spacious den, with several others in the kitchen and another dining area. I stood in the den, with my cousins, our backs to the covered patio, with a clear view of the foyer and the front door.

As the woman yodeled, my father suddenly catapulted from the dining room into the living, straddling a broom like it was a toy horse. He sported a bright smile and waved to the crowd in the den. Those of us who saw him burst into hysterical laughter, while those closer to the kitchen, against the fireplace, or against the wall parallel to the entertainment duo jumped to their feet. They clustered en masse in the center of the den, just in time to see my dad gallop back across the foyer into the dining room. The woman singing saw him on the return jaunt and almost lost control of her voice.

It’s those moments that kept circulating through my mind these past several days, as my father, George De La Garza, began his transition into his next life. It began last Monday, June 6. After enduring an array of health problems over the past few years, capped by two weeks in the hospital just last month, he’d finally had enough. We had a brief memorial service Saturday morning, the 11th, at a local funeral home. Both my parents were wise to make funeral arrangements five years ago. They had initially bought cemetery plots, but decided afterwards to be cremated and sold the plots back to the funeral home. My father didn’t want an extended funeral; no real funeral at all, in fact, with a Catholic rosary, a lengthy mass, a parade of limousines and another service at the grave site. His philosophy was simple: “just throw me in a box, toss me into the ground, say your prayers and go on with your own lives.”

I had written of my father previously, but he didn’t like too much attention bestowed upon him. He was a unique character who liked to make people laugh and who often made himself the butt of his own jokes. As a teenager, he’d often play pranks on his mother, Francisca. Once she sent him to the store with a list of items to buy. He left the house briefly and sneaked back inside and went into his parents’ bedroom; where he called the home phone number. In those days, if you had more than one phone in the house, you could actually call your own number from within, and the other phone would ring. His mother picked up the phone in the kitchen. My father pretended to be at the store and confused by what she’d written on the list. He aggravated her, until finally he set down the bedroom phone and startled her by walking into the kitchen.

My paternal grandparents had eleven children, but four of them – two boys and two girls – died either as infants or toddlers. That was common in those days – couples would have several kids and some may die not long after birth. But my father often said his parents had so many kids because his mother was hard of hearing. As they got ready for bed, my grandfather would ask, “Well, do you want to go to sleep, or what?” And my grandmother would respond, “What?”

My mother certainly didn’t escape his humorous wraths. He told me that she and her younger sister, Angie, were so mean and bitter because they’d grown up in México picking avocadoes. When their father decided to move the family to the U.S. in 1943, my father said, he could only afford train fare for four people. So he went, along with his oldest daughter, his son and his mother-in-law. For my mother and Angie, according to my dad, my grandfather leased a donkey and told them just to ride north until you run into bunch of White people speaking only English.

Like most men, he was fiercely protective of his family. My mother told me years ago that, if my father knew how some of the men talked to her at the insurance companies where she worked her entire life, he’d probably be in prison; meaning, he’d most certainly kill more than a few. He always said he’d know I would be a boy. One particular picture he took of me as an infant, he said, was the mirror image of what he’d dreamed about while my mother was still pregnant. She almost lost me twice during what she said was a 10-month pregnancy and was in labor for several hours. While they languished at the hospital, the staff was trying to reach the pediatrician; this being a time before pagers and cell phones. When he finally showed up, my father asked where he’d been.

“What’s the big deal?” replied the doctor. “You have a date tonight?” I guess he was trying to be cute.

But my father – usually catching the humor in someone’s tone of voice – grabbed the man by the lapels of his jacket and slammed him up against a nearby wall. “Listen, you bastard! My wife is in pain, and I want to know what the hell you’re going to do about it!”

My dad could still find some way to turn a bad situation around. During the extended funeral of John F. Kennedy, my parents had gathered with other friends and relatives at the home of my father’s older brother, Jesse, and his wife, Helen. At one point, Helen asked why the “flags were halfway up the poles.”

“Because they ran out of string,” answered my father.

About fifteen or so years ago, my parents agreed to watch the pet goldfish belonging to the daughters of some neighbors; a younger couple who are about my age. One day my mother changed the water in the fish bowl. The next day the fish were dead. My parents hurried to a pet store to buy two more goldfish; hoping the neighbors wouldn’t notice. But those fish also died. My father told me what happened, adding, “Damn! I didn’t know I was married to a serial killer!”

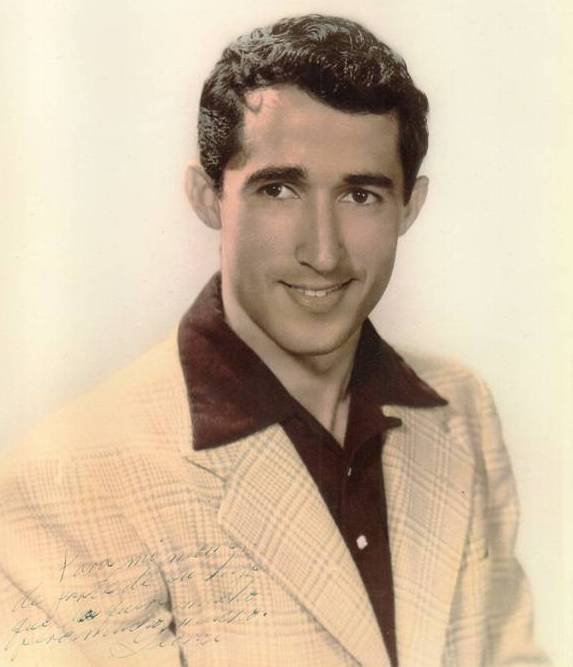

I stare at pictures of my father scattered throughout the house and notice, in almost all of them, he’s smiling and / or laughing. He was that rare type who never met a stranger. Unlike me, he was an extrovert. I always admired that about him. He could never understand why it was so hard for me to make friends.

His health had begun to take a more dramatic turn for the worst at the end of 2014. Following a partial colectomy, he was hospitalized twice for kidney failure. He vowed he’d never allow himself to be taken to the hospital again. “I want to die here at home.”

But, one weekday morning a month ago, he had a change of mind. “I think I need to go the hospital. I want to live.”

So I called 911 and had him hospitalized. He again was suffering from kidney failure, but this time, his gall bladder had also become infected. They got him as stable as possible, and after two weeks, I convinced the doctors to let him go. Technically, from a medical standpoint, he wasn’t actually ready to be released. But I made it quite clear to all the attending physicians that he needed to be home.

I had asked him only once the previous week, if he wanted to go back to the hospital. He shook his head no. He knew this was it. The end for him was near. I knew it as well, but I was still trying to get him healthy. It’s so difficult to see a loved one in the grip of such physical agony. It was so tough to see a man who radiated vitality – even into his 70s – gasping for air and barely able to move. I had prayed for his suffering to end. And we all know the old saying, ‘Be careful for what you wish for; you might just get it.’ Short of a miraculous recovery, my father’s health just wasn’t going to improve.

He wanted to die at home. He wanted to pass away in the house he and my mother had worked so hard to buy and to keep. And I wanted to grant him that wish.

My dog, Wolfgang, who will turn 14 this week, initially wandered throughout the house looking for my father. Then, over the past few days, I noticed that something seemed to be catching his attention. He’d suddenly sit up or prick up his ears. And then relax. I believe animals possess a stronger sensory perception than we humans. It’s their one superior trait.

My grandmother Francisca died in February of 2001, almost three years to the day after the death of her eldest daughter, my Aunt Amparo. The next two deaths were my Aunt Teresa and my Uncle Jesse, both in 2004. Several months after Jesse’s death, my father had a strange dream that he couldn’t explain until after he told me about it. He was perched on a tractor lawn mower, plowing through a large expanse of grass, when he noticed a group people perched beneath a tree. As he got closer, he realized they were his parents and three older siblings. He could see his father completely, but he could only see the top halves of his mother and Amparo. Teresa was covered by a black veil, and Jesse was off to one side, shrouded in darkness.

My grandfather motioned for him to come closer and then asked him if he wished to join them. Was he – in effect – ready to give up on this life? My father said he turned to the field of grass and said no – he had too much work to do. And then he woke up.

I realized the grass was a metaphor for all of the things my father still wanted to do in his life. It was symbolic, too, because he loved gardening. I also realized that – as my father had described them – the family’s appearances represented their time on the other side. His father had died in 1969, so his spirit had time to metamorphose into what was a familiar figure. His mother and Amparo had only died a few years earlier. Teresa and Jesse and arrived on that side the year before, so their spirits hadn’t had enough time to take shape into people he’d recognize. He only knew it was them because they each spoke to him.

I don’t believe the human soul has any definite shape, color or mass. It’s not like what we see here. I’m also much more spiritual, even though I started off the memorial service with the Lord’s Prayer. I want to pray to my father to help me through the ensuing difficulties with my mother. He’s just begun his transition into that new life, however; so I don’t want to disturb him too much. Allow me to be greedy, though. I miss him terribly. My heart still aches, but I’m more at ease now than I have been in over this past week.

On Sunday night, June 5, my father kept pointing forward and uttering something. After a minute or so, I finally understood what he was saying, “Door.” There was a door in front of him; not the bedroom door. That other door. He was finally able to step through it. And that’s what needed to happen. At some point in time, we all step through that door. No one really dies. The body perishes, but the good souls remain alive.

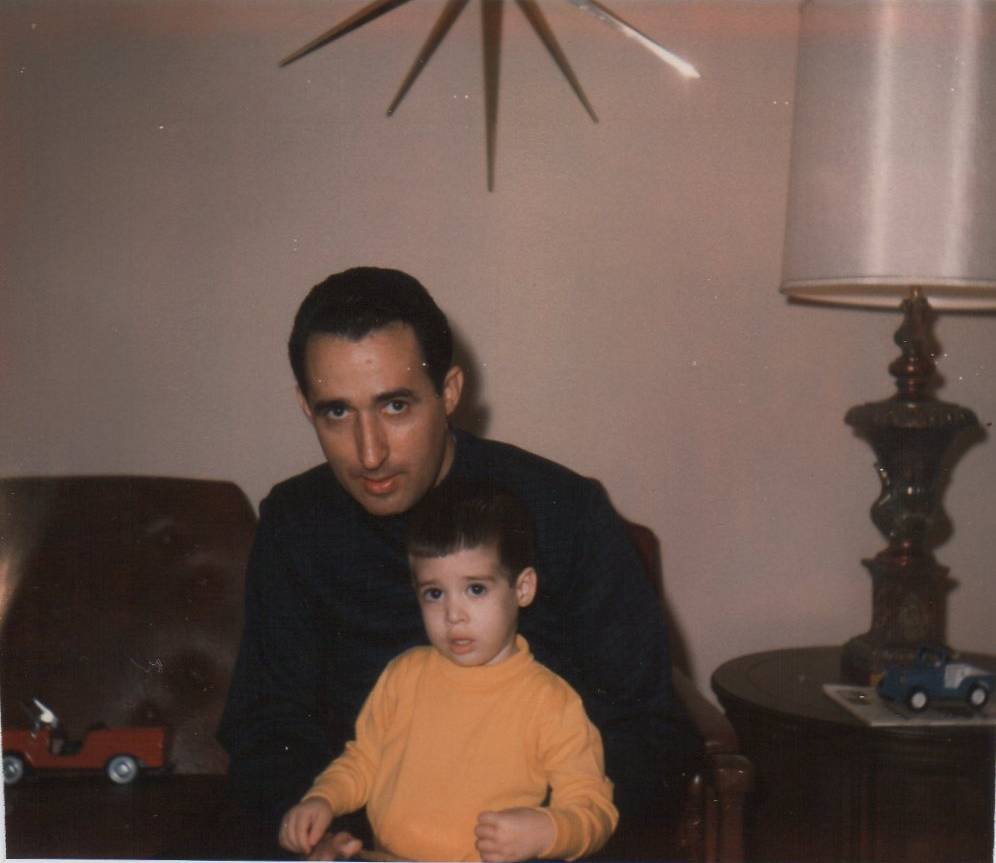

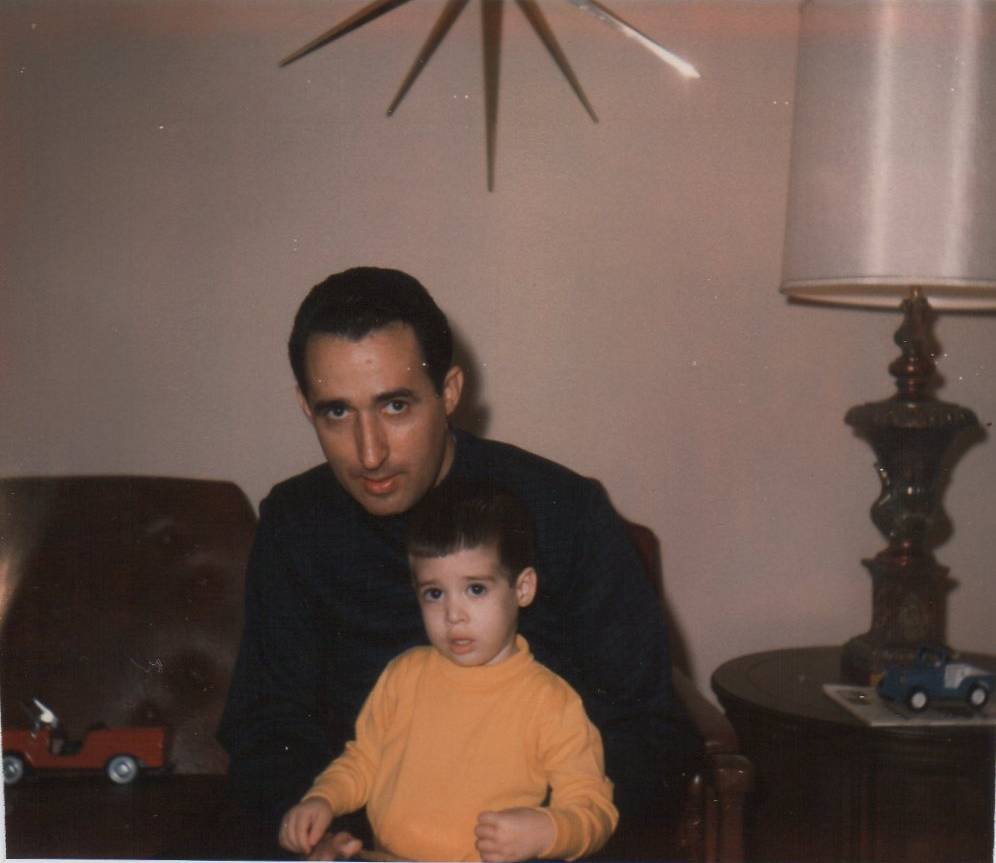

My father and me in 1966.